Category Archives: Analize stanja

Mastnak: Ali je vstajniško gibanje idejno šibko?

Tomaž Mastnak: Legitimno in smiselno je razmisliti o izstopu iz EU

S sociologom Tomažem Mastnakom smo se pogovarjali o krizi demokracije s strašljivimi obeti totalitarizmov na obzorju.

Vstajniško gibanje je po lanskem začetnem zagonu letos spomladi usahnilo, čeravno razlogov za nezadovoljstvo ne manjka, prej nasprotno. Kako si razlagate implozijo tega gibanja?

Ne vem, morda gre le za začasen usih ali umik. Imam pa vtis, da gibanje nima organizacijske strukture, ki bi mu omogočala kontinuirano delovanje, in morda je to eden od razlogov, da trenutno ni protestov. Morda pa kontinuirano delovanje niti ni bilo namen gibanja ali njegovih delov. Poleg tega je res, da je bil eden glavnih ciljev gibanja – odstop vlade Janeza Janše – izpolnjen. Uresničitev tega cilja je verjetno veliko prispevala k temu, da so protesti vsaj za nekaj časa ponehali. Na čelu vlade, ki je padla, je bil človek, ki ga je bilo zelo lahko sovražiti, tako rekoč idealna figura za tovrstne proteste, kar je delovalo mobilizacijsko. Zdaj so ta človek in njegova garnitura stopili v ozadje, kjer še naprej delajo tako, kot so navajeni delati. Ostali so sestavni del slovenske politike, njen pomembni del.

Slovenska politika je še naprej taka, kot je bila pred padcem Janševe vlade, slovenski politični prostor se ni spremenil. A zdaj to ni več motivacija za proteste. Zdaj je na čelu vlade oseba, ki ne vzbuja – ali vsaj še ne – omembe vrednega sovraštva. To seveda ne pomeni, da ni razlogov za proteste proti vladi. Navsezadnje v politiki sedanje vlade ne opazim nobene velike diskontinuitete s politiko njene predhodnice. To so sile kontinuitete ne z neko mistično komunistično preteklostjo, temveč s prejšnjo vlado.

Je razlog za usahnitev protestov tudi idejna šibkost vstajniškega gibanja, ki izhaja že iz tega, da je bila osrednja zahteva gibanja negativna: odstop politične elite?

V negativnosti zahtev ne vidim nujno šibkosti gibanja. Prej v tem, da kljub govorjenju o alternativnih politikah, alternativnih oblikah organiziranja družbe in tako naprej nisem zasledil ničesar, kar bi me prepričalo, da tovrstne zamisli ne le obstajajo, marveč da se na njih resno dela – razen neumnosti o neposredni demokraciji. Zame problem namreč ni, da nimamo neposredne demokracije, temveč da reprezentativna demokracija ne deluje več. Reprezentativna demokracija je v krizi, iz katere se verjetno ne bo nikdar več izvlekla. Ljudje, ki naj bi bili naši predstavniki, pa to niso več, so si organizirali neposredno demokracijo, toda ta, tako kot starogrška neposredna demokracija, temelji na suženjstvu, na novodobnem suženjstvu.

Potem imamo tu, kot sem lahko zasledil, demokratični socializem. Nič nimam proti socializmu. No, socializem, ki se ga gre vladajoča manjšina, ko socializira svoje polomije in izgube z nadaljnjo privatizacijo družbenega bogastva, ni po mojem okusu. Koliko je v geslu demokratičnega socializma politike, pa ne vem. Koliko politike in kakšno politiko nosi s sabo ali v sebi? Je to sploh politično geslo? Ker sem doktrinar, se sprašujem tudi, kakšen smisel ima zagovarjati demokratični socializem v času zatona demokracije. Zakaj ne bi raje zagovarjali resničnega socializma? Pred kratkim sem prebiral Rheinische Jahrbücher zur gesellschaftlichen Reform – zanimivo branje! Ampak to je zgodovina. In včasih se ne morem otresti vtisa, da je ta alternativni demokratični socializem zgrajen na zgodovinski amneziji. Kdor ima amnezijo, lahko vsak dan izve kaj novega, ampak to ni nujno novost za tiste okrog njega.

Ko gre za ekonomske politike, ni dovolj bentiti čez neoliberalizem. Oznaka je največkrat ohlapna, pogosto služi za to, da se olajšamo. Utegne biti tudi zavajajoča, neredko napelje k temu, da smo že v rehabilitaciji liberalizma pripravljeni videti alternativo. Kaj pa če neoliberalizem ni drugega kot simptom smrti liberalizma? Liberalizem je mrtev. Rabimo alternativo liberalni ekonomiji, prav tako politiki. Ekvivokacije med skupnostno lastnino, commons, in komunizmom so dobrodošle, kolikor prispevajo k spremembi perspektive, niso pa alternativni program. Lotiti se moramo anatomije politično-ekonomskega sistema, ki je prevladoval zadnje stoletje in pol, in na tej ravni artikulirati alternative. Zamisli o trajnostnem razvoju, denimo, kažejo v pravo smer, a ta jezik si že prilaščajo tudi nosilci destruktivnih ekonomskih in političnih praks. Vem, da so zagovorniki trajnostno usmerjenega gospodarstva bili na demonstracijah, ni mi pa znano, da bi se o tem razpravljalo v okviru protestov. Vesel bi bil, če sem le slabo informiran.

Naj dodam še nekaj. Če je idejna šibkost, ki ste jo omenili v vprašanju, v resnici slabost slovenskega protestniškega gibanja, nikakor ni samo njegova slabost. Pustimo ob strani, da so današnje politične elite popolnoma intelektualno zbankrotirane. Če privzamemo, da so protestniška gibanja pretežno levo usmerjena, je treba reči, da je intelektualna šibkost obča lastnost levice v svetovnem merilu. Levica je doživela intelektualni kolaps, katerega začetki verjetno segajo že v osemdeseta leta prejšnjega stoletja, in od njega si še ni opomogla. Zato ponuja le malenkost sfrizirano različico tiste iste politike, ki jo vsiljujejo njeni principielni nasprotniki.

Teršek: Avtoritarni legalizem in vstajništvo

Vstajniško gibanje in retorika oblasti

AVTORITARNI LEGALIZEM SLOVENSKEGA PRAVOSODJA

Razlogi za osebno, državljansko in poklicno zaskrbljenost zaradi slovenskih pravnih praks se stopnjujejo dnevno. Uradniških in sodniških odločitev, pri katerih bode v oči ugotovitev, da njihovi avtorji temeljnih (ustavno)pravnih in pravnofilozofskih konceptov, načel in doktrin ne razumejo dovolj dobro, je enostavno preveč. Ta problem, ki je tudi posledica nekaterih pomanjkljivosti pravnega študija in odprave sprejemnih izpitov za vpis na pravne fakultete, postaja preobsežen. Ustavne pravice in svoboščine so zato alarmantno ogrožene. Ob tem pa grožnje ne predstavlja samo nedojemljivost prevelikega števila posameznikov na uradniških in sodniških funkcijah za težja ali celo težka pravna vprašanja. Prav neverjetno je, koliko oblastnih odločitev ni usklajenih s tistimi pravili, načeli in učenji v pravu, ki jih gre razumeti kot pravno abecedo ali slovnico. Največja težava pri tem je, da lahko takšne oblastne odločitve, uradniške ali sodniške, močno škodijo tistim ljudem, ki jih neposredno zadevajo. Zanje imajo lahko tudi eksistenčni pomen. In prav takšnih odločitev je znatno preveč.

Imam privilegij, da se lahko dnevno srečujem s tovrstnimi mrtvimi rokavi slovenskega pravosodja in stiskami ljudi. Ob tem pa prepoznavam bolečo in izčrpavajočo dvojnost stisk. Ne gre namreč samo za to, da posameznik pred oblastnimi organi ne doseže tistega, kar upravičeno terja kot svojo pravico, ali da se mu odreče tisto, kar nedvomno je njegova pravica. Gre tudi za to, da oblastne odločitve, ki niso samo strokovno nevzdržne, ampak so tudi nelogične, nerazumljive, nerazumne, kratkovidne ali takšne, da iz človeka izvabijo besedo »neumne«, žalijo posameznikovo dostojanstvo in imajo lahko močan vpliv na njegovo zdravstveno dobrobit. Nemalokrat se zgodi, da si ljudje, ki vedo, da pred oblastnimi organi in sodnimi instancami ne morejo več doseči tistega, kar bi si želeli in kar jim pripada, želijo samo pogovora, ob katerem bi dobili potrditev, da imajo prav, da razmišljajo zdravo, da njihov razum ni poškodovan in da njihova miselna integriteta ni ogrožena. Takšna potrditev jim zadošča, da kljub doživeti krivici v postopkih institucionaliziranega odločanja živijo dalje, pragmatično sprijaznjeni in notranje pomirjeni.

Oblastne odločitve pogosto presegajo življenja posameznikov in imajo sistemski pomen. Mislim na to, da ne pomenijo le odgovora na konkretno vprašanje iz življenja konkretnega posameznika, ampak odražajo institucionalni odnos predstavnikov državnega aparata do sistemskih ali celo metavprašanj. Oblastne odločitve so lahko prikaz, kako družba razume samo sebe skozi prizmo oblastnih institucij in kako ljudje, v različnih oblastnih statusih in vlogah, razumejo razmerje med institucionalnim ustrojem družbe na eni strani in posameznikom kot osebo na drugi. Dogajanje ob legitimnih protestih, odnos najvišjih predstavnikov oblasti do protestov in protestnikov, pa tudi nedavna obsodba sedmih vstajnikov na zaporno kazen je takšen primer.

Retorika oblasti, s katero sta vodstvo ministrstva za notranje zadeve in policije naslavljala protestniško dogajanje in vstajniško gibanje, pomeni poskus kriminalizacije protestnih ravnanj in vstajniškega gibanja. Drža nosilcev oblastnih funkcij je bila policijska drža. Nosilci oblastnih funkcij, pristojnih za notranje zadeve, so udejanjali pristope in uporabljali jezik policijske države. Tisti predstavniki pravne stroke, ki so bili neprepričljivi pri poskusu javnega zanikanja svojega izrazitega političnega navijaštva, so se sklicevali na sicer ustavna načela in koncepte z grobim pravnim formalizmom in zakonskim legalizmom. Mirne in miroljubne protestnike, ki so uresničevali ustavno pravico do javnega političnega protesta, se je ne le pozivalo k »upoštevanju ukazov policije« in razhodu, ampak tudi prisilno odganjalo s prizorišča, celo preganjalo. Javna in spontana protestna zborovanja se je poskušalo pogojevati s predhodnimi najavami in formalnimi organiziranji. Marsikateri sedeči protestnik je bil deležen tepeža. Zoper miroljubne protestnike so bili zato, ker so na politično pomembnem protestnem kraju javno, glasno in mirno protestirali, sproženi postopki zaradi domnevnih storitev prekrškov in celo kaznivih dejanj. Sindikatom je bila naložena globa z očitkom o soorganiziranju in spodbujanju protestov. Vodstvu javne univerze je bila izrečena globa zaradi protestno sklenjenih rok okrog univerzitetne palače. Dokazi o politično načrtovanem provociranju ljudi so bili prepričljivi. In še bi lahko naštevali. To so poteze, to je obraz policijske države. Pravosodje ne bi smelo ponuditi roke državi pri institucionalni zaščiti ukrepov policijske države. Oziroma pri kriminalizaciji protesta, protestnikov in vstajništva.

Znameniti ustavnopravni filozof prof. Ronald Dworkin je v svojih delih pojasnjeval, da je posameznik upravičen, da ravna na podlagi lastne vesti in iskrene presoje. Menil je, da ima ob tem država posebno dolžnost, da poskuša zavarovati prav tega delujočega posameznika in mu olajšati težavnost položaja, v katerem se je znašel npr. zaradi protesta, če to lahko stori brez povzročanja velike škode drugim legitimnim političnim interesom. Seveda država takšnemu posamezniku ne more zagotoviti popolne imunitete. Država se ne more zavezati, da ne bo preganjala nikogar, ki deluje na podlagi svoje vesti, ali da ne bo obsojala nikogar, ki razumno ne soglaša z oblastno odločitvijo. Če država, pojasnjuje Dworkin, primerov sicer razumnega nestrinjanja in neprivolitve v oblastne odločitve ali dejanj posameznikov, ki jih usmerja njihova vest, ne bi nikdar kaznovala, potem tudi sodišča svojih odločitev ne bi mogla utemeljevati z izkušnjami in argumenti, ki so jih v svojih dejanjih političnega protesta izpostavili kritiki obstoječih družbenih dejstev in okoliščin. Vendarle pa bi po njegovem mnenju morala država v primerih obstoja zgolj šibkih dejanskih razlogov, ki bi opravičevali pregon neposlušnih posameznikov, ali v primerih, ko se država lahko z njimi sooči na drugačen, nekaznovalen način, bistvo pravičnosti iskati v načelu tolerance. Dworkin poudari, da načelo »zakon je pač zakon in ga je treba vselej spoštovati« odklanja razlikovanje med tistimi, ki delujejo na podlagi njihove lastne sodbe o sicer dvomljivi pravni zapovedi, in tistimi, ki jih je mogoče enostavno označiti kot kriminalce.

Omenjeno razlikovanje je smiselno, pravi, če ne želimo ostati moralno slepi. Dworkin je, podobno kot znameniti John Rawls, menil, da zahtevajo primeri civilne neposlušnosti drugačen, modificiran kazenski pregon. Sodišča bi morala državljanom dati vedeti, da državljanska neposlušnost ni eden od običajnih deliktov. Družba si tudi po njegovem mnenju ne more zagotoviti trajnosti, če je prizanesljiva do vseh pojavov neposlušnosti, iz česar pa ni mogoče sklepati, da bo prišlo do kolapsa družbe, če bo prizanesljiva do nekaterih pojavov neposlušnosti. In ob nekem izjemnem primeru, ko na primer odpove ustava, mora pogosto prav država dati svojo legalnost na razpolago tistim, ki so potem sposobni skrbeti tudi za njeno legitimnost.

Odločitev o tem, kdaj tak položaj nastane, ne more biti odvisna od ugotovitve nekega oblastnega organa. Nasprotno, običajno je prav takšen organ razlog ali predmet civilne neposlušnosti in kritike oslabele, nezadostne legitimnosti. O tem naprej odloča predvsem posameznik, upoštevaje svoj lastni čut za politično odgovornost in etične temelje družbenega reda. V končni fazi pa tudi tisti del družbene skupnosti, na katerega se posameznik obrača v svojem apelu za dvig stopnje politične legitimnosti in univerzalne družbene pravičnosti. Če sodna veja ne spoštuje dostojanstva in legitimnosti dejanj civilne neposlušnosti, poudarja Dworkin, če kršilce pravnih pravil sodišča pavšalno in po pozitivističnem avtomatizmu preganjajo kot kriminalce ter jih obsojajo na običajne kazni, podlegajo »avtoritarnemu legalizmu«. Na ta način sodišča izražajo svoje togo in rigidno konvencionalno razumevanje države. Sodišča s tem na izrazito negativen način posegajo v moralne temelje družbe ter njeno politično kulturo. Država ne bo obnovila spoštovanja do prava, če ne bo pravu samemu omogočila pozivanja k spoštovanju. Tega ne more storiti, če spregleda prav tisto, kar pravo razlikuje od zaukazane brutalnosti. Če država pravic ne jemlje resno, potem tudi prava ne more jemati resno, je bil prepričan Dworkin.

Avtomatizirani legalizem slovenskega pravosodja je tudi z ozirom na pravico do protesta, upora in vstajništvo protiustaven.

_

Dr. Andraž Teršek je ustavnik, zaposlen na Univerzi na Primorskem.

Pogledi, let. 4, št. 18, 25. september 2013

Damijan o evru – bombi

Kaj mora narediti Merklova, da EU ne konča kot Jugoslavija?

Britanski Economist ne slepomiši in se ne pretvarja, da nima političnih preferenc. Ponavadi pa pred pomembnimi volitvami javno in argumentirano da ali odtegne svojo podporo posameznemu politiku – denimo za Obamo ali proti Berlusconiju. V zadnji številki je dal jasno podporo Angeli Merkel na nemških zveznih volitvah. Pri tem je jasno povedal, zakaj je Merklovo v zadnjih letih stalno kritiziral v zvezi z njeno kontroverzno vlogo pri reševanju krize (preveč varčevanja, vendar kljub vsemu ohranitev Grčije na evrskem območju). Toda hkrati je povedal, da je Merklova vseeno najbolj nadarjena političarka med demokrati v svetovnem merilu in trenutno najboljša izbira v Nemčiji. Merklova bi lahko postala dominantni evropski politik in oseba, ki bo reformirala EU v zvezo konkurenčnih držav.

Tokrat se z Economistom ne strinjam. Zaradi strukturnih razlogov. Še več, če bo EU nadaljevala zdajšnjo ekonomsko politiko, bo končala kot nekdanja Jugoslavija. Morda bolj civilizirano (brez vojnih spopadov), toda v solzah. Preden se preveč razburite in me primerjate z Mencingerjem, preberite do konca.

Kaj je bila nekdanja Jugoslavija? Bila je simetrična monetarna unija držav na zelo različnih razvojnih stopnjah, v katero so napumpali velikanske količine ideologije (edinstven socializem, bratstvo in enotnost) ter okovali v oklep politične in vojaške diktature, da bi jo obdržali skupaj. Nekdanja Jugoslavija je imela skupno valuto, prost pretok blaga, storitev in kapitala ter veliko mobilnost delovne sile, toda hkrati tudi netržne mehanizme, ki so pomagali k notranji stabilizaciji ob asimetričnih krizah. Bila je tudi transferna unija (da sploh ne omenjam bančne unije). Imela je mehanizme za pretok regionalnih pomoči, na podlagi katerih so se pretakala sredstva od bolj razvitih k manj razvitim. In imela je skupni zvezni proračun, ki je po potrebi lahko prerazporejal sredstva med republikami (denimo za brezposelne, za socialne transferje…) ob asimetričnih šokih v posameznih delih države. Nekdanja Jugoslavija je bila simetrična denarna unija. Nekaj podobnega kot ZDA brez socialistične ideologije in enopartijske diktature kot veziva. Toda kljub vsemu je končala v ognju in solzah.

Kaj je EU? EU je asimetrična denarna unija, brez bančne in z izjemno šibko transferno unijo, brez ideologije kot veziva ter z zelo medlo opredeljenimi skupnimi evropskimi vrednotami. Brez dneva mladosti, brez dneva republike in brez skupne reprezentance denimo v nogometu. Če EU jutri razpade, je čustveno ne bo nihče pogrešal. Toda glavna razlika med EU in Jugoslavijo ali ZDA je v njeni asimetričnosti. V EU imamo prost pretok blaga, delno prost pretok storitev in kapitala ter zelo omejeno mobilnost delovne sile. Zaradi katastrofalne krize v mediteranskih članicah EU se Grki, Španci, Portugalci in Italijani ne bodo v desetinah milijonov preselili v zahodne članice, kar bi zmanjšalo vprašanje brezposelnosti v državah, bolj prizadetih s krizo. V nekdanji Jugoslaviji ali ZDA je ta mehanizem deloval oziroma deluje. Še več, v obeh je deloval (deluje) mehanizem transferjev za brezposelne in socialno pomoč prek zveznega proračuna. V EU tega mehanizma ni. V času krize je vsaka država odvisna samo od sebe. Vsaka država mora poskrbeti za svoje brezposelne in potrebne socialne pomoči. EU ima le mehanizem regionalnih pomoči, ki nekoliko preprečuje, da bi se razlike v razvitosti še bolj povečale.

|

Če bo EU nadaljevala zdajšnjo ekonomsko politiko, bo končala kot nekdanja Jugoslavija. Morda bolj civilizirano (brez vojnih spopadov), toda v solzah.

|

Glavna težava EU kot denarne unije je v tem, da je v svojem bistvu enaka zlatemu standardu. Zlatega standarda pa, kot vam bo povedala vsaka makroekonomska knjiga ali knjiga o ekonomski zgodovini, ni mogoče vzdrževati v demokraciji. Ker je srednjeročno socialno nevzdržen. Evro ni nič drugega kot dogovor držav, da tečaj svoje domače valute fiksirajo na neko vnaprej določeno razmerje do drugih valut ter se hkrati odpovejo svoji valuti. EU je s tem eksperimentirala že od sedemdesetih let. Vendar so se vsi poskusi, da bi državam uspelo vzdrževati to fiksno razmerje med valutami, klavrno končali. Imeli smo evropski mehanizem deviznih tečajev 1 (ERM 1), pa kačo (v tunelu in zunaj tunela) in imeli smo ERM 2, pa ni nič pomagalo. V času krize so posamezne države morale devalvirati, spremeniti razmerje svoje valute do preostalih ter tako podražiti uvoz in povečati izvozno konkurenčnost. Po tej poti so države lahko preprečile razmah krize in znižale brezposelnost. To je bil njihov ventil, ki so ga lahko uporabile v skrajni sili. Hkrati so lahko po potrebi še natiskale denarja, kolikor so hotele.

Nato je, po dveh desetletjih ponesrečenih poskusov denarnega povezovanja, sredi devetdesetih let prišla politična odločitev za skupno evropsko valuto. Toda celotni koncept skupne valute je bil že v jedru invalidno oblikovan – kot asimetrična denarna unija. Torej s skupno valuto, vendar brez transfernih mehanizmov in brez centralne banke, ki bi brezrezervno stala s svojo tiskarno denarja za obveznostmi držav članic (kot to denimo počnejo centralne banke Velike Britanije, Japonske, ZDA…). Preprosto rečeno, države so se odpovedale možnosti, da po potrebi devalvirajo svojo valuto ali tiskajo denar, v zameno za to pa niso dobile nobenega mehanizma, ki bi jim pomagal, če jih zadane asimetrični šok, kot ga doživljajo mediteranske države zdaj. Evro je bil, tako kot projekcije naših tajkunskih menedžerjev o prihodnji rasti, oblikovan samo za dobre čase. O možnosti slabih časov politiki niso hoteli razmišljati. Pa vendar so intelektualni očetje evra, kot je denimo profesor Paul de Grauwe, prav na to ves čas opozarjali. Prav tako, vsi po vrsti, ameriški ekonomisti. Asimetrična denarna unija je predeterminirana za propad. Prav nobene možnosti nima.

Zakaj? Zato, ker skupna valuta v osnovi predvideva, da so vsa gospodarstva podobno razvita, imajo podobno gospodarsko sestavo in so podobno produktivna, kar pomeni, da imajo tudi podobne stopnje gospodarske rasti in podobne stopnje inflacije. Biti v denarni uniji skupaj z Nemčijo in njenim gospodarskim strojem pa pomeni, da morajo imeti vse preostale članice enako produktivna gospodarstva. Evro pomeni, da moramo biti vsi Nemci. Vsi moramo proizvajati enako kakovostne avtomobile in strojno opremo kot Nemci. Kar pa je seveda težko. Še teže pa je bilo, ker je imela Nemčija ves čas podcenjeno valuto ter počasnejšo rast plač in inflacije. To pomeni, da je Nemčija še hitreje povečevala relativno produktivnost in imela nižjo stopnjo inflacije, kar pa je razlike samo še povečevalo – do nevzdržnosti.

Kriza, ki jo evrsko območje doživlja v zadnjih petih letih, ni (kot nekateri povsem zmotno in na pamet trdijo) posledica okužbe z ameriško finančno krizo. Kriza evrskega območja je bila vgrajena v sam dizajn evropske denarne unije in bi se zgodila tudi brez ameriškega vpliva. Propad Lehman Brothers in nenadna osušitev mednarodnih veleprodajnih (repo) posojilnih trgov sta krizo evrskega območja samo sprožila in nato pospešila njen razvoj. Kriza evrskega območja je preprosto posledica dveh značilnosti evrske denarne unije.

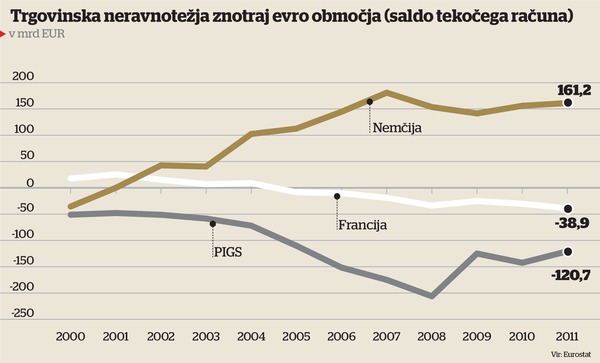

Prvič, kriza je posledica nemške večje rasti produktivnosti glede na večino preostalih članic in proste notranje trgovine ter posledično naraščajočega trgovinskega presežka Nemčije na eni strani in trgovinskega primanjkljaja preostalih članic na drugi. Takoj po uvedbi evra je začel nemški trgovinski presežek s preostalimi članicami močno naraščati. Nemčija je bila pred desetletjem v veliki krizi; zamrznila je plače in sprostila trg dela ter s tem povečala svojo konkurenčnost, preostale države pa so veselo uvažale iz Nemčije. Druge države temu niso mogle slediti, kljub prestrukturiranju v storitveni sektor in povečanemu izvozu storitev. Do uvedbe evra je samo Francija imela presežek na tekočem računu (bilanca menjave blaga, storitev in dohodkov). Tudi Nemčija je imela primanjkljaj. Po uvedbi evra je Nemčija začela ustvarjati velik presežek na tekočem računu, vse preostale članice evrskega območja pa povečevati svoj primanjkljaj. Z letom 2005 je tudi Francija zašla v primanjkljaj. Kot kaže graf, je nemški trgovinski presežek zgolj zrcalna slika velikega trgovinskega primanjkljaja držav PIGS, pa tudi Francije. Ali z drugimi besedami: evro je omogočil Nemčiji širitev na račun uvoza drugih članic. Da je Nemčija lahko neto izvažala, so morali vsi drugi neto uvažati.

|

S temi trgovinskimi primanjkljaji, kot kaže primer ZDA, ni načeloma nič narobe, dokler ga države lahko financirajo. Drugi glavni dejavnik evrske krize so zato finančni tokovi znotraj Unije. Pred uvedbo evra so finančni trgi države različno vrednotili glede na njihove fundamente (proračunski saldo in javni dolg glede na BDP). Z uvedbo evra pa so finančni trgi povsem spremenili optiko – nenadoma so zaradi učinka skupne valute začeli ocenjevati posojilno tveganje Španije, Portugalske, Italije ali Grčije precej ugodneje kot prej. Začeli so vse članice ocenjevati skoraj, kot da so vse Nemčija. Po letu 2001 so razponi zahtevanih donosov na državne obveznice držav z evrom močno konvergirali. V ozadju je bila (lažna) predpostavka, da za državne obveznice vsake članice implicitno jamči ECB. Nenadoma so naložbe v obveznice Grčije, Španije in drugih držav postale izjemno privlačne, saj so ob zmanjšanjem tveganju omogočale večji donos od denimo nemških obveznic. Evropske banke so trumoma kupovale obveznice obrobnih evrskih držav.

Od kod je prišel denar? Če poznate osnove makroekonomije, vam seveda ni neznano, da se presežek države v zunanji trgovini (natančneje: na tekočem računu plačilne bilance) po definiciji pokaže na drugi strani kot povečanje prihrankov. Domačini manj porabijo, kot proizvedejo. Država, ki je neto izvoznica (blaga in storitev), je hkrati tudi neto izvoznica kapitala. Po domače, svoje prihranke plasira v tujino. In natanko to so počele nemške banke pred krizo. Še več, temu so se pridružile tudi francoske banke in oboje so se množično »čez noč« zadolževale na veleprodajnih (repo) finančnih trgih in s temi sredstvi množično kupovale donosne vrednostne papirje obrobnih držav EU ter te »zelo varne« vrednostne papirje (saj naj bi za njimi stala ECB) uporabile kot kritje za množično podeljevanje (dolgoročnih) posojil. Posojil, s katerimi so španski porabniki kupovali nemške izdelke ali irski nepremičninarji gradili stanovanjske komplekse. To je bila orgija za francoske in nemške banke. Orgija brez pokritja.

Če mislite, da so imele ZDA težavo z bankami, se motite. Ameriški bančni sektor je pred krizo znašal samo 130 odstotkov BDP, bilančna vsota šestih največjih ameriških bank leta 2008 je znašala le 61 odstotkov BDP. Nasprotno pa je bilančna vsota zgolj treh največjih francoskih bank leta 2008 znašala 316 odstotkov francoskega BDP. Bilančna vsota dveh največjih nemških bank pa je znašala 114 odstotkov nemškega BDP, pri čemer je samo Deutsche Bank imela sredstev v vrednosti 80 odstotkov nemškega BDP. Medtem ko so bile ameriške banke prevelike, da bi jih pustili propasti (too big to fail), so, kot pravi Mark Blyth, evropske banke postale prevelike, da bi jih bilo mogoče rešiti (too big to bail). Ko so se po bankrotu Lehman Borothers veleprodajni finančni trgi posušili, se je zgodilo natanko to. Države z evrom so po finančni orgiji ostale z velikanskimi bančnimi težavami, na prvem mestu Francija in Nemčija. Reševanje Grčije je bilo predvsem reševanje nemških in francoskih bank, ki so nasedle z nenadoma visoko tveganimi vrednostnimi papirji držav PIGS v svojih bilancah. Podobno velja za Irsko in Španijo.

Težava bi bila z lahkoto rešljiva, če bi takoj ob izbruhu krize ECB opravila svojo nalogo in jamčila za obveznosti držav PIGS. Tako kot Fed jamči za ameriške državne obveznice. Toda temu je Nemčija absolutno nasprotovala, češ da ne bo jamčila za »življenje prek lastnih zmožnosti« drugih članic. Kar je seveda hinavščina, saj je prav trošenje v obrobnih državah omogočilo nemškemu gospodarstvu trgovinski presežek, nemškim bankam pa velike dobičke. Težava bi bila rešljiva tudi, če bi države PIGS lahko izstopile iz evra in devalvirale svoje valute ter tako povečale svojo zunanjo konkurenčnost. Toda te možnosti niso imele.

Namesto tega so dobile »nemško dieto« – strogo varčevanje. Prej proračunsko vzorne države, kot sta Španija in Irska, so prevzele obveznosti svojih bank do njihovih posojilodajalk v Nemčiji in Franciji, zaradi česar se je povečal njihov javni dolg. Nato pa ista Nemčija zahteva, da države zategnejo pas svojim državljanom, ki seveda niso bili krivi za orgijo niti domačih bank niti tujih, ki so posojale domačim. Pri tem je najhujše predvsem dejstvo, da takšna skupinska politika varčevanja v času krize preprosto ne more delovati. Če podjetja ne vlagajo, če porabniki nočejo trošiti in če država ne sme trošiti, ostane samo še izvoz, ki bi lahko potegnil gospodarstvo iz recesije. Ker pa ne trošijo porabniki tudi v drugih državah, seveda tudi izvoz ne more rasti.

Nobene reforme na trgu dela, nobene pokojninske reforme v posameznih članicah ne morejo rešiti temeljne težave – da preostale članice ne morejo slediti Nemčiji po rasti produktivnosti in nizki inflaciji. Lahko samo malce ublažijo težavo. Ob nadaljevanju politike varčevanja se bodo države samo izstradale, poviševala se bo brezposelnost, prav tako pa zadolženost držav. Nekoč bo seveda spet prišlo do rasti, toda za izjemno visoko ceno izgubljenih delovnih mest in izgubljenega dohodka.

Toda preden se bo to zgodilo, obstaja verjetna nevarnost, da EU politično razpade. Socialni stroški reševanja krize po nemškem receptu so previsoki. Občutno previsoki za demokracije. Ali lahko socialni nemiri posamezne članice prej ali slej prisilijo, da izstopijo iz evra, kar bi za seboj potegnilo plaz? To bi pomenilo, da je na kocki 60 let političnega projekta združevanja Evrope. Ali lahko celoten projekt propade zaradi ene rešitve, pri kateri vztraja Nemčija?

Rešitev za evro bi bila, če bi Nemčija spremenila svojo ekonomsko politiko, denimo dvignila plače, znižala davke in s tem spodbudila porabo, na drugi strani pa dvignila inflacijo. S tem bi nemško gospodarstvo postalo manj konkurenčno, zdajšnji trgovinski presežek Nemčije pa bi se spremenil v ekvivalenten primanjkljaj. Tako bi Nemčija omogočila preostalim članicam, da se dvignejo iz recesije.

Ali se to lahko zgodi? Ocenjujem, da ne. Ali zato evrskim članicam, preden začnejo individualno izstopati iz evra, preostane le varianta, da zagrozijo s kolektivnim izstopom iz evra? Od tu naprej bi se našle rešitve, kot je uvedba »nacionalnih evrov« (kar de facto pomeni vrnitev k nacionalnim valutam, le pod drugim imenom), ki bi omogočile posameznim državam potrebno prožnost in mehanizem za stabilizacijo v času kriz. To bi ohranilo EU kot gospodarsko unijo in kot politični projekt.

Ali je Angela Merkel pravi človek za ta posel? Ali ima širino in evropsko vizijo, ki so jo imeli nekdanji nemški in francoski voditelji? Odgovor na to vprašanje je odgovor na vprašanje, ali bo EU končala po »jugoslovansko«.

|

Podrobnosti zakulisja afere Snowden – dokumentaristka Laura Poitras – The background of the Snowden case

<nyt_text>

This past January, Laura Poitras received a curious e-mail from an anonymous stranger requesting her public encryption key. For almost two years, Poitras had been working on a documentary about surveillance, and she occasionally received queries from strangers. She replied to this one and sent her public key — allowing him or her to send an encrypted e-mail that only Poitras could open, with her private key — but she didn’t think much would come of it.

Q. & A.: Edward Snowden Speaks to Peter Maass

Why he turned to Poitras and Greenwald.

Readers’ Comments

Share your thoughts.

The stranger responded with instructions for creating an even more secure system to protect their exchanges. Promising sensitive information, the stranger told Poitras to select long pass phrases that could withstand a brute-force attack by networked computers. “Assume that your adversary is capable of a trillion guesses per second,” the stranger wrote.

Before long, Poitras received an encrypted message that outlined a number of secret surveillance programs run by the government. She had heard of one of them but not the others. After describing each program, the stranger wrote some version of the phrase, “This I can prove.”

Seconds after she decrypted and read the e-mail, Poitras disconnected from the Internet and removed the message from her computer. “I thought, O.K., if this is true, my life just changed,” she told me last month. “It was staggering, what he claimed to know and be able to provide. I just knew that I had to change everything.”

Poitras remained wary of whoever it was she was communicating with. She worried especially that a government agent might be trying to trick her into disclosing information about the people she interviewed for her documentary, including Julian Assange, the editor of WikiLeaks. “I called him out,” Poitras recalled. “I said either you have this information and you are taking huge risks or you are trying to entrap me and the people I know, or you’re crazy.”

The answers were reassuring but not definitive. Poitras did not know the stranger’s name, sex, age or employer (C.I.A.? N.S.A.? Pentagon?). In early June, she finally got the answers. Along with her reporting partner, Glenn Greenwald, a former lawyer and a columnist for The Guardian, Poitras flew to Hong Kong and met the N.S.A. contractor Edward J. Snowden, who gave them thousands of classified documents, setting off a major controversy over the extent and legality of government surveillance. Poitras was right that, among other things, her life would never be the same.

Greenwald lives and works in a house surrounded by tropical foliage in a remote area of Rio de Janeiro. He shares the home with his Brazilian partner and their 10 dogs and one cat, and the place has the feel of a low-key fraternity that has been dropped down in the jungle. The kitchen clock is off by hours, but no one notices; dishes tend to pile up in the sink; the living room contains a table and a couch and a large TV, an Xbox console and a box of poker chips and not much else. The refrigerator is not always filled with fresh vegetables. A family of monkeys occasionally raids the banana trees in the backyard and engages in shrieking battles with the dogs.

Mauricio Lima for The New York Times

Glenn Greenwald, a writer for The Guardian, at home in Rio de Janeiro.

Greenwald does most of his work on a shaded porch, usually dressed in a T-shirt, surfer shorts and flip-flops. Over the four days I spent there, he was in perpetual motion, speaking on the phone in Portuguese and English, rushing out the door to be interviewed in the city below, answering calls and e-mails from people seeking information about Snowden, tweeting to his 225,000 followers (and conducting intense arguments with a number of them), then sitting down to write more N.S.A. articles for The Guardian, all while pleading with his dogs to stay quiet. During one especially fever-pitched moment, he hollered, “Shut up, everyone,” but they didn’t seem to care.

Amid the chaos, Poitras, an intense-looking woman of 49, sat in a spare bedroom or at the table in the living room, working in concentrated silence in front of her multiple computers. Once in a while she would walk over to the porch to talk with Greenwald about the article he was working on, or he would sometimes stop what he was doing to look at the latest version of a new video she was editing about Snowden. They would talk intensely — Greenwald far louder and more rapid-fire than Poitras — and occasionally break out laughing at some shared joke or absurd memory. The Snowden story, they both said, was a battle they were waging together, a fight against powers of surveillance that they both believe are a threat to fundamental American liberties.

Two reporters for The Guardian were in town to assist Greenwald, so some of our time was spent in the hotel where they were staying along Copacabana Beach, the toned Brazilians playing volleyball in the sand below lending the whole thing an added layer of surreality. Poitras has shared the byline on some of Greenwald’s articles, but for the most part she has preferred to stay in the background, letting him do the writing and talking. As a result, Greenwald is the one hailed as either a fearless defender of individual rights or a nefarious traitor, depending on your perspective. “I keep calling her the Keyser Soze of the story, because she’s at once completely invisible and yet ubiquitous,” Greenwald said, referring to the character in “The Usual Suspects” played by Kevin Spacey, a mastermind masquerading as a nobody. “She’s been at the center of all of this, and yet no one knows anything about her.”

As dusk fell one evening, I followed Poitras and Greenwald to the newsroom of O Globo, one of the largest newspapers in Brazil. Greenwald had just published an article there detailing how the N.S.A. was spying on Brazilian phone calls and e-mails. The article caused a huge scandal in Brazil, as similar articles have done in other countries around the world, and Greenwald was a celebrity in the newsroom. The editor in chief pumped his hand and asked him to write a regular column; reporters took souvenir pictures with their cellphones. Poitras filmed some of this, then put her camera down and looked on. I noted that nobody was paying attention to her, that all eyes were on Greenwald, and she smiled. “That’s right,” she said. “That’s perfect.”

Poitras seems to work at blending in, a function more of strategy than of shyness. She can actually be remarkably forceful when it comes to managing information. During a conversation in which I began to ask her a few questions about her personal life, she remarked, “This is like visiting the dentist.” The thumbnail portrait is this: She was raised in a well-off family outside Boston, and after high school, she moved to San Francisco to work as a chef in upscale restaurants. She also took classes at the San Francisco Art Institute, where she studied under the experimental filmmaker Ernie Gehr. In 1992, she moved to New York and began to make her way in the film world, while also enrolling in graduate classes in social and political theory at the New School. Since then she has made five films, most recently “The Oath,” about the Guantánamo prisoner Salim Hamdan and his brother-in-law back in Yemen, and has been the recipient of a Peabody Award and a MacArthur award.

On Sept. 11, 2001, Poitras was on the Upper West Side of Manhattan when the towers were attacked. Like most New Yorkers, in the weeks that followed she was swept up in both mourning and a feeling of unity. It was a moment, she said, when “people could have done anything, in a positive sense.” When that moment led to the pre-emptive invasion of Iraq, she felt that her country had lost its way. “We always wonder how countries can veer off course,” she said. “How do people let it happen, how do people sit by during this slipping of boundaries?” Poitras had no experience in conflict zones, but in June 2004, she went to Iraq and began documenting the occupation.

Shortly after arriving in Baghdad, she received permission to go to Abu Ghraib prison to film a visit by members of Baghdad’s City Council. This was just a few months after photos were published of American soldiers abusing prisoners there. A prominent Sunni doctor was part of the visiting delegation, and Poitras shot a remarkable scene of his interaction with prisoners there, shouting that they were locked up for no good reason.

The doctor, Riyadh al-Adhadh, invited Poitras to his clinic and later allowed her to report on his life in Baghdad. Her documentary, “My Country, My Country,” is centered on his family’s travails — the shootings and blackouts in their neighborhood, the kidnapping of a nephew. The film premiered in early 2006 and received widespread acclaim, including an Oscar nomination for best documentary.

Attempting to tell the story of the war’s effect on Iraqi citizens made Poitras the target of serious — and apparently false — accusations. On Nov. 19, 2004, Iraqi troops, supported by American forces, raided a mosque in the doctor’s neighborhood of Adhamiya, killing several people inside. The next day, the neighborhood erupted in violence. Poitras was with the doctor’s family, and occasionally they would go to the roof of the home to get a sense of what was going on. On one of those rooftop visits, she was seen by soldiers from an Oregon National Guard battalion. Shortly after, a group of insurgents launched an attack that killed one of the Americans. Some soldiers speculated that Poitras was on the roof because she had advance notice of the attack and wanted to film it. Their battalion commander, Lt. Col. Daniel Hendrickson, retired, told me last month that he filed a report about her to brigade headquarters.

There is no evidence to support this claim. Fighting occurred throughout the neighborhood that day, so it would have been difficult for any journalist to not be near the site of an attack. The soldiers who made the allegation told me that they have no evidence to prove it. Hendrickson told me his brigade headquarters never got back to him.

For several months after the attack in Adhamiya, Poitras continued to live in the Green Zone and work as an embedded journalist with the U.S. military. She has screened her film to a number of military audiences, including at the U.S. Army War College. An officer who interacted with Poitras in Baghdad, Maj. Tom Mowle, retired, said Poitras was always filming and it “completely makes sense” she would film on a violent day. “I think it’s a pretty ridiculous allegation,” he said.

Although the allegations were without evidence, they may be related to Poitras’s many detentions and searches. Hendrickson and another soldier told me that in 2007 — months after she was first detained — investigators from the Department of Justice’s Joint Terrorism Task Force interviewed them, inquiring about Poitras’s activities in Baghdad that day. Poitras was never contacted by those or any other investigators, however. “Iraq forces and the U.S. military raided a mosque during Friday prayers and killed several people,” Poitras said. “Violence broke out the next day. I am a documentary filmmaker and was filming in the neighborhood. Any suggestion I knew about an attack is false. The U.S. government should investigate who ordered the raid, not journalists covering the war.”

In June 2006, her tickets on domestic flights were marked “SSSS” — Secondary Security Screening Selection — which means the bearer faces extra scrutiny beyond the usual measures. She was detained for the first time at Newark International Airport before boarding a flight to Israel, where she was showing her film. On her return flight, she was held for two hours before being allowed to re-enter the country. The next month, she traveled to Bosnia to show the film at a festival there. When she flew out of Sarajevo and landed in Vienna, she was paged on the airport loudspeaker and told to go to a security desk; from there she was led to a van and driven to another part of the airport, then taken into a room where luggage was examined.

“They took my bags and checked them,” Poitras said. “They asked me what I was doing, and I said I was showing a movie in Sarajevo about the Iraq war. And then I sort of befriended the security guy. I asked what was going on. He said: ‘You’re flagged. You have a threat score that is off the Richter scale. You are at 400 out of 400.’ I said, ‘Is this a scoring system that works throughout all of Europe, or is this an American scoring system?’ He said. ‘No, this is your government that has this and has told us to stop you.’ ”

After 9/11, the U.S. government began compiling a terrorist watch list that was at one point estimated to contain nearly a million names. There are at least two subsidiary lists that relate to air travel. The no-fly list contains the names of tens of thousands of people who are not allowed to fly into or out of the country. The selectee list, which is larger than the no-fly list, subjects people to extra airport inspections and questioning. These lists have been criticized by civil rights groups for being too broad and arbitrary and for violating the rights of Americans who are on them.

In Vienna, Poitras was eventually cleared to board her connecting flight to New York, but when she landed at J.F.K., she was met at the gate by two armed law-enforcement agents and taken to a room for questioning. It is a routine that has happened so many times since then — on more than 40 occasions — that she has lost precise count. Initially, she said, the authorities were interested in the paper she carried, copying her receipts and, once, her notebook. After she stopped carrying her notes, they focused on her electronics instead, telling her that if she didn’t answer their questions, they would confiscate her gear and get their answers that way. On one occasion, Poitras says, they did seize her computers and cellphones and kept them for weeks. She was also told that her refusal to answer questions was itself a suspicious act. Because the interrogations took place at international boarding crossings, where the government contends that ordinary constitutional rights do not apply, she was not permitted to have a lawyer present.

“It’s a total violation,” Poitras said. “That’s how it feels. They are interested in information that pertains to the work I am doing that’s clearly private and privileged. It’s an intimidating situation when people with guns meet you when you get off an airplane.”

Though she has written to members of Congress and has submitted Freedom of Information Act requests, Poitras has never received any explanation for why she was put on a watch list. “It’s infuriating that I have to speculate why,” she said. “When did that universe begin, that people are put on a list and are never told and are stopped for six years? I have no idea why they did it. It’s the complete suspension of due process.” She added: “I’ve been told nothing, I’ve been asked nothing, and I’ve done nothing. It’s like Kafka. Nobody ever tells you what the accusation is.”

After being detained repeatedly, Poitras began taking steps to protect her data, asking a traveling companion to carry her laptop, leaving her notebooks overseas with friends or in safe deposit boxes. She would wipe her computers and cellphones clean so that there would be nothing for the authorities to see. Or she encrypted her data, so that law enforcement could not read any files they might get hold of. These security preparations could take a day or more before her travels.

It wasn’t just border searches that she had to worry about. Poitras said she felt that if the government was suspicious enough to interrogate her at airports, it was also most likely surveilling her e-mail, phone calls and Web browsing. “I assume that there are National Security Letters on my e-mails,” she told me, referring to one of the secretive surveillance tools used by the Department of Justice. A National Security Letter requires its recipients — in most cases, Internet service providers and phone companies — to provide customer data without notifying the customers or any other parties. Poitras suspected (but could not confirm, because her phone company and I.S.P. would be prohibited from telling her) that the F.B.I. had issued National Security Letters for her electronic communications.

Conor Provenzano

Laura Poitras filming the construction of a large N.S.A. facility in Utah.

Once she began working on her surveillance film in 2011, she raised her digital security to an even higher level. She cut down her use of a cellphone, which betrays not only who you are calling and when, but your location at any given point in time. She was careful about e-mailing sensitive documents or having sensitive conversations on the phone. She began using software that masked the Web sites she visited. After she was contacted by Snowden in 2013, she tightened her security yet another notch. In addition to encrypting any sensitive e-mails, she began using different computers for editing film, for communicating and for reading sensitive documents (the one for sensitive documents is air-gapped, meaning it has never been connected to the Internet).

These precautions might seem paranoid — Poitras describes them as “pretty extreme” — but the people she has interviewed for her film were targets of the sort of surveillance and seizure that she fears. William Binney, a former top N.S.A. official who publicly accused the agency of illegal surveillance, was at home one morning in 2007 when F.B.I. agents burst in and aimed their weapons at his wife, his son and himself. Binney was, at the moment the agent entered his bathroom and pointed a gun at his head, naked in the shower. His computers, disks and personal records were confiscated and have not yet been returned. Binney has not been charged with any crime.

Jacob Appelbaum, a privacy activist who was a volunteer with WikiLeaks, has also been filmed by Poitras. The government issued a secret order to Twitter for access to Appelbaum’s account data, which became public when Twitter fought the order. Though the company was forced to hand over the data, it was allowed to tell Appelbaum. Google and a small I.S.P. that Appelbaum used were also served with secret orders and fought to alert him. Like Binney, Appelbaum has not been charged with any crime.

Poitras endured the airport searches for years with little public complaint, lest her protests generate more suspicion and hostility from the government, but last year she reached a breaking point. While being interrogated at Newark after a flight from Britain, she was told she could not take notes. On the advice of lawyers, Poitras always recorded the names of border agents and the questions they asked and the material they copied or seized. But at Newark, an agent threatened to handcuff her if she continued writing. She was told that she was being barred from writing anything down because she might use her pen as a weapon.

“Then I asked for crayons,” Poitras recalled, “and he said no to crayons.”

She was taken into another room and interrogated by three agents — one was behind her, another asked the questions, the third was a supervisor. “It went on for maybe an hour and a half,” she said. “I was taking notes of their questions, or trying to, and they yelled at me. I said, ‘Show me the law where it says I can’t take notes.’ We were in a sense debating what they were trying to forbid me from doing. They said, ‘We are the ones asking the questions.’ It was a pretty aggressive, antagonistic encounter.”

Poitras met Greenwald in 2010, when she became interested in his work on WikiLeaks. In 2011, she went to Rio to film him for her documentary. He was aware of the searches and asked several times for permission to write about them. After Newark, she gave him a green light.

“She said, ‘I’ve had it,’ ” Greenwald told me. “Her ability to take notes and document what was happening was her one sense of agency, to maintain some degree of control. Documenting is what she does. I think she was feeling that the one vestige of security and control in this situation had been taken away from her, without any explanation, just as an arbitrary exercise of power.”

At the time, Greenwald was a writer for Salon. His article, “U.S. Filmmaker Repeatedly Detained at Border,” was published in April 2012. Shortly after it was posted, the detentions ceased. Six years of surveillance and harassment, Poitras hoped, might be coming to an end.

Poitras was not Snowden’s first choice as the person to whom he wanted to leak thousands of N.S.A. documents. In fact, a month before contacting her, he reached out to Greenwald, who had written extensively and critically about the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and the erosion of civil liberties in the wake of 9/11. Snowden anonymously sent him an e-mail saying he had documents he wanted to share, and followed that up with a step-by-step guide on how to encrypt communications, which Greenwald ignored. Snowden then sent a link to an encryption video, also to no avail.

“It’s really annoying and complicated, the encryption software,” Greenwald said as we sat on his porch during a tropical drizzle. “He kept harassing me, but at some point he just got frustrated, so he went to Laura.”

Snowden had read Greenwald’s article about Poitras’s troubles at U.S. airports and knew she was making a film about the government’s surveillance programs; he had also seen ashort documentary about the N.S.A. that she made for The New York Times Op-Docs. He figured that she would understand the programs he wanted to leak about and would know how to communicate in a secure way.

By late winter, Poitras decided that the stranger with whom she was communicating was credible. There were none of the provocations that she would expect from a government agent — no requests for information about the people she was in touch with, no questions about what she was working on. Snowden told her early on that she would need to work with someone else, and that she should reach out to Greenwald. She was unaware that Snowden had already tried to contact Greenwald, and Greenwald would not realize until he met Snowden in Hong Kong that this was the person who had contacted him more than six months earlier.

There were surprises for everyone in these exchanges — including Snowden, who answered questions that I submitted to him through Poitras. In response to a question about when he realized he could trust Poitras, he wrote: “We came to a point in the verification and vetting process where I discovered Laura was more suspicious of me than I was of her, and I’m famously paranoid.” When I asked him about Greenwald’s initial silence in response to his requests and instructions for encrypted communications, Snowden replied: “I know journalists are busy and had assumed being taken seriously would be a challenge, especially given the paucity of detail I could initially offer. At the same time, this is 2013, and [he is] a journalist who regularly reported on the concentration and excess of state power. I was surprised to realize that there were people in news organizations who didn’t recognize any unencrypted message sent over the Internet is being delivered to every intelligence service in the world.”

In April, Poitras e-mailed Greenwald to say they needed to speak face to face. Greenwald happened to be in the United States, speaking at a conference in a suburb of New York City, and the two met in the lobby of his hotel. “She was very cautious,” Greenwald recalled. “She insisted that I not take my cellphone, because of this ability the government has to remotely listen to cellphones even when they are turned off. She had printed off the e-mails, and I remember reading the e-mails and felt intuitively that this was real. The passion and thought behind what Snowden — who we didn’t know was Snowden at the time — was saying was palpable.”

Greenwald installed encryption software and began communicating with the stranger. Their work was organized like an intelligence operation, with Poitras as the mastermind. “Operational security — she dictated all of that,” Greenwald said. “Which computers I used, how I communicated, how I safeguarded the information, where copies were kept, with whom they were kept, in which places. She has this complete expert level of understanding of how to do a story like this with total technical and operational safety. None of this would have happened with anything near the efficacy and impact it did, had she not been working with me in every sense and really taking the lead in coordinating most of it.”

Snowden began to provide documents to the two of them. Poitras wouldn’t tell me when he began sending her documents; she does not want to provide the government with information that could be used in a trial against Snowden or herself. He also said he would soon be ready to meet them. When Poitras asked if she should plan on driving to their meeting or taking a train, Snowden told her to be ready to get on a plane.

In May, he sent encrypted messages telling the two of them to go to Hong Kong. Greenwald flew to New York from Rio, and Poitras joined him for meetings with the editor of The Guardian’s American edition. With the paper’s reputation on the line, the editor asked them to bring along a veteran Guardian reporter, Ewen MacAskill, and on June 1, the trio boarded a 16-hour flight from J.F.K. to Hong Kong.

Snowden had sent a small number of documents to Greenwald, about 20 in all, but Poitras had received a larger trove, which she hadn’t yet had the opportunity to read closely. On the plane, Greenwald began going through its contents, eventually coming across a secret court order requiring Verizon to give its customer phone records to the N.S.A. The four-page order was from the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, a panel whose decisions are highly classified. Although it was rumored that the N.S.A. was collecting large numbers of American phone records, the government always denied it.

Poitras, sitting 20 rows behind Greenwald, occasionally went forward to talk about what he was reading. As the man sitting next to him slept, Greenwald pointed to the FISA order on his screen and asked Poitras: “Have you seen this? Is this saying what I’m thinking it’s saying?”

At times, they talked so animatedly that they disturbed passengers who were trying to sleep; they quieted down. “We couldn’t believe just how momentous this occasion was,” Greenwald said. “When you read these documents, you get a sense of the breadth of them. It was a rush of adrenaline and ecstasy and elation. You feel you are empowered for the first time because there’s this mammoth system that you try and undermine and subvert and shine a light on — but you usually can’t make any headway, because you don’t have any instruments to do it — [and now] the instruments were suddenly in our lap.”

Snowden had instructed them that once they were in Hong Kong, they were to go at an appointed time to the Kowloon district and stand outside a restaurant that was in a mall connected to the Mira Hotel. There, they were to wait until they saw a man carrying a Rubik’s Cube, then ask him when the restaurant would open. The man would answer their question, but then warn that the food was bad. When the man with the Rubik’s Cube arrived, it was Edward Snowden, who was 29 at the time but looked even younger.

“Both of us almost fell over when we saw how young he was,” Poitras said, still sounding surprised. “I had no idea. I assumed I was dealing with somebody who was really high-level and therefore older. But I also knew from our back and forth that he was incredibly knowledgeable about computer systems, which put him younger in my mind. So I was thinking like 40s, somebody who really grew up on computers but who had to be at a higher level.”

In our encrypted chat, Snowden also remarked on this moment: “I think they were annoyed that I was younger than they expected, and I was annoyed that they had arrived too early, which complicated the initial verification. As soon as we were behind closed doors, however, I think everyone was reassured by the obsessive attention to precaution and bona fides.”

They followed Snowden to his room, where Poitras immediately shifted into documentarian mode, taking her camera out. “It was a little bit tense, a little uncomfortable,” Greenwald said of those initial minutes. “We sat down, and we just started chatting, and Laura was immediately unpacking her camera. The instant that she turned on the camera, I very vividly recall that both he and I completely stiffened up.”

Greenwald began the questioning. “I wanted to test the consistency of his claims, and I just wanted all the information I could get, given how much I knew this was going to be affecting my credibility and everything else. We weren’t really able to establish a human bond until after that five or six hours was over.”

For Poitras, the camera certainly alters the human dynamic, but not in a bad way. When someone consents to being filmed — even if the consent is indirectly gained when she turns on the camera — this is an act of trust that raises the emotional stakes of the moment. What Greenwald saw as stilted, Poitras saw as a kind of bonding, the sharing of an immense risk. “There is something really palpable and emotional in being trusted like that,” she said.

Snowden, though taken by surprise, got used to it. “As one might imagine, normally spies allergically avoid contact with reporters or media, so I was a virgin source — everything was a surprise. . . . But we all knew what was at stake. The weight of the situation actually made it easier to focus on what was in the public interest rather than our own. I think we all knew there was no going back once she turned the camera on.”

For the next week, their preparations followed a similar pattern — when they entered Snowden’s room, they would remove their cellphone batteries and place them in the refrigerator of Snowden’s minibar. They lined pillows against the door, to discourage eavesdropping from outside, then Poitras set up her camera and filmed. It was important to Snowden to explain to them how the government’s intelligence machinery worked because he feared that he could be arrested at any time.

Greenwald’s first articles — including the initial one detailing the Verizon order he read about on the flight to Hong Kong — appeared while they were still in the process of interviewing Snowden. It made for a strange experience, creating the news together, then watching it spread. “We could see it being covered,” Poitras said. “We were all surprised at how much attention it was getting. Our work was very focused, and we were paying attention to that, but we could see on TV that it was taking off. We were in this closed circle, and around us we knew that reverberations were happening, and they could be seen and they could be felt.”

Snowden told them before they arrived in Hong Kong that he wanted to go public. He wanted to take responsibility for what he was doing, Poitras said, and he didn’t want others to be unfairly targeted, and he assumed he would be identified at some point. She made a 12½-minute video of him that was posted online June 9, a few days after Greenwald’s first articles. It triggered a media circus in Hong Kong, as reporters scrambled to learn their whereabouts.

There were a number of subjects that Poitras declined to discuss with me on the record and others she wouldn’t discuss at all — some for security and legal reasons, others because she wants to be the first to tell crucial parts of her story in her own documentary. Of her parting with Snowden once the video was posted, she would only say, “We knew that once it went public, it was the end of that period of working.”

Snowden checked out of his hotel and went into hiding. Reporters found out where Poitras was staying — she and Greenwald were at different hotels — and phone calls started coming to her room. At one point, someone knocked on her door and asked for her by name. She knew by then that reporters had discovered Greenwald, so she called hotel security and arranged to be escorted out a back exit.

She tried to stay in Hong Kong, thinking Snowden might want to see her again, and because she wanted to film the Chinese reaction to his disclosures. But she had now become a figure of interest herself, not just a reporter behind the camera. On June 15, as she was filming a pro-Snowden rally outside the U.S. consulate, a CNN reporter spotted her and began asking questions. Poitras declined to answer and slipped away. That evening, she left Hong Kong.

Philippe Lopez/AFP/Getty Images

A protest in Hong Kong in support of Edward Snowden on June 15.

Poitras flew directly to Berlin, where the previous fall she rented an apartment where she could edit her documentary without worrying that the F.B.I. would show up with a search warrant for her hard drives. “There is a filter constantly between the places where I feel I have privacy and don’t,” she said, “and that line is becoming increasingly narrow.” She added: “I’m not stopping what I’m doing, but I have left the country. I literally didn’t feel like I could protect my material in the United States, and this was before I was contacted by Snowden. If you promise someone you’re going to protect them as a source and you know the government is monitoring you or seizing your laptop, you can’t actually physically do it.”

After two weeks in Berlin, Poitras traveled to Rio, where I then met her and Greenwald a few days later. My first stop was the Copacabana hotel, where they were working that day with MacAskill and another visiting reporter from The Guardian, James Ball. Poitras was putting together a new video about Snowden that would be posted in a few days on The Guardian’s Web site. Greenwald, with several Guardian reporters, was working on yet another blockbuster article, this one about Microsoft’s close collaboration with the N.S.A.The room was crowded — there weren’t enough chairs for everyone, so someone was always sitting on the bed or floor. A number of thumb drives were passed back and forth, though I was not told what was on them.

Poitras and Greenwald were worried about Snowden. They hadn’t heard from him since Hong Kong. At the moment, he was stuck in diplomatic limbo in the transit area of Moscow’s Sheremetyevo airport, the most-wanted man on the planet, sought by the U.S. government for espionage. (He would later be granted temporary asylum in Russia.) The video that Poitras was working on, using footage she shot in Hong Kong, would be the first the world had seen of Snowden in a month.

“Now that he’s incommunicado, we don’t know if we’ll even hear from him again,” she said.

“Is he O.K.?” MacAskill asked.

“His lawyer said he’s O.K.,” Greenwald responded.

“But he’s not in direct contact with Snowden,” Poitras said

When Greenwald got home that evening, Snowden contacted him online. Two days later, while she was working at Greenwald’s house, Poitras also heard from him.

It was dusk, and there was loud cawing and hooting coming from the jungle all around. This was mixed with the yapping of five or six dogs as I let myself in the front gate. Through a window, I saw Poitras in the living room, intently working at one of her computers. I let myself in through a screen door, and she glanced up for just a second, then went back to work, completely unperturbed by the cacophony around her. After 10 minutes, she closed the lid of her computer and mumbled an apology about needing to take care of some things.

She showed no emotion and did not mention that she had been in the middle of an encrypted chat with Snowden. At the time, I didn’t press her, but a few days later, after I returned to New York and she returned to Berlin, I asked if that’s what she was doing that evening. She confirmed it, but said she didn’t want to talk about it at the time, because the more she talks about her interactions with Snowden, the more removed she feels from them.

“It’s an incredible emotional experience,” she said, “to be contacted by a complete stranger saying that he was going to risk his life to expose things the public should know. He was putting his life on the line and trusting me with that burden. My experience and relationship to that is something that I want to retain an emotional relation to.” Her connection to him and the material, she said, is what will guide her work. “I am sympathetic to what he sees as the horror of the world [and] what he imagines could come. I want to communicate that with as much resonance as possible. If I were to sit and do endless cable interviews — all those things alienate me from what I need to stay connected to. It’s not just a scoop. It’s someone’s life.”

Poitras and Greenwald are an especially dramatic example of what outsider reporting looks like in 2013. They do not work in a newsroom, and they personally want to be in control of what gets published and when. When The Guardian didn’t move as quickly as they wanted with the first article on Verizon, Greenwald discussed taking it elsewhere, sending an encrypted draft to a colleague at another publication. He also considered creating a Web site on which they would publish everything, which he planned to call NSADisclosures. In the end, The Guardian moved ahead with their articles. But Poitras and Greenwald have created their own publishing network as well, placing articles with other outlets in Germany and Brazil and planning more for the future. They have not shared the full set of documents with anyone.

“We are in partnership with news organizations, but we feel our primary responsibility is to the risk the source took and to the public interest of the information he has provided,” Poitras said. “Further down on the list would be any particular news organization.”

Unlike many reporters at major news outlets, they do not attempt to maintain a facade of political indifference. Greenwald has been outspoken for years; on Twitter, he recently replied to one critic by writing: “You are a complete idiot. You know that, right?” His left political views, combined with his cutting style, have made him unloved among many in the political establishment. His work with Poitras has been castigated as advocacy that harms national security. “I read intelligence carefully,” said Senator Dianne Feinstein, chairwoman of the Senate Intelligence Committee, shortly after the first Snowden articles appeared. “I know that people are trying to get us. . . . This is the reason the F.B.I. now has 10,000 people doing intelligence on counterterrorism. . . . It’s to ferret this out before it happens. It’s called protecting America.”

Poitras, while not nearly as confrontational as Greenwald, disagrees with the suggestion that their work amounts to advocacy by partisan reporters. “Yes, I have opinions,” she told me. “Do I think the surveillance state is out of control? Yes, I do. This is scary, and people should be scared. A shadow and secret government has grown and grown, all in the name of national security and without the oversight or national debate that one would think a democracy would have. It’s not advocacy. We have documents that substantiate it.”

Poitras possesses a new skill set that is particularly vital — and far from the journalistic norm — in an era of pervasive government spying: she knows, as well as any computer-security expert, how to protect against surveillance. As Snowden mentioned, “In the wake of this year’s disclosure, it should be clear that unencrypted journalist-source communication is unforgivably reckless.” A new generation of sources, like Snowden or Pfc. Bradley Manning, has access to not just a few secrets but thousands of them, because of their ability to scrape classified networks. They do not necessarily live in and operate through the established Washington networks — Snowden was in Hawaii, and Manning sent hundreds of thousands of documents to WikiLeaks from a base in Iraq. And they share their secrets not with the largest media outlets or reporters but with the ones who share their political outlook and have the know-how to receive the leaks undetected.

In our encrypted chat, Snowden explained why he went to Poitras with his secrets: “Laura and Glenn are among the few who reported fearlessly on controversial topics throughout this period, even in the face of withering personal criticism, [which] resulted in Laura specifically becoming targeted by the very programs involved in the recent disclosures. She had demonstrated the courage, personal experience and skill needed to handle what is probably the most dangerous assignment any journalist can be given — reporting on the secret misdeeds of the most powerful government in the world — making her an obvious choice.”

Snowden’s revelations are now the center of Poitras’s surveillance documentary, but Poitras also finds herself in a strange, looking-glass dynamic, because she cannot avoid being a character in her own film. She did not appear in or narrate her previous films, and she says that probably won’t change with this one, but she realizes that she has to be represented in some way, and is struggling with how to do that.

She is also assessing her legal vulnerability. Poitras and Greenwald are not facing any charges, at least not yet. They do not plan to stay away from America forever, but they have no immediate plans to return. One member of Congress has already likened what they’ve done to a form of treason, and they are well aware of the Obama administration’s unprecedented pursuit of not just leakers but of journalists who receive the leaks. While I was with them, they talked about the possibility of returning. Greenwald said that the government would be unwise to arrest them, because of the bad publicity it would create. It also wouldn’t stop the flow of information.

He mentioned this while we were in a taxi heading back to his house. It was dark outside, the end of a long day. Greenwald asked Poitras, “Since it all began, have you had a non-N.S.A. day?”

“What’s that?” she replied.

“I think we need one,” Greenwald said. “Not that we’re going to take one.”

Poitras talked about getting back to yoga again. Greenwald said he was going to resume playing tennis regularly. “I’m willing to get old for this thing,” he said, “but I’m not willing to get fat.”

Their discussion turned to the question of coming back to the United States. Greenwald said, half-jokingly, that if he was arrested, WikiLeaks would become the new traffic cop for publishing N.S.A. documents. “I would just say: ‘O.K., let me introduce you to my friend Julian Assange, who’s going to take my place. Have fun dealing with him.’ ”

Poitras prodded him: “So you’re going back to the States?”

He laughed and pointed out that unfortunately, the government does not always take the smartest course of action. “If they were smart,” he said, “I would do it.”

Poitras smiled, even though it’s a difficult subject for her. She is not as expansive or carefree as Greenwald, which adds to their odd-couple chemistry. She is concerned about their physical safety. She is also, of course, worried about surveillance. “Geolocation is the thing,” she said. “I want to keep as much off the grid as I can. I’m not going to make it easy for them. If they want to follow me, they are going to have to do that. I am not going to ping into any G.P.S. My location matters to me. It matters to me in a new way that I didn’t feel before.”

There are lots of people angry with them and lots of governments, as well as private entities, that would not mind taking possession of the thousands of N.S.A. documents they still control. They have published only a handful — a top-secret, headline-grabbing, Congressional-hearing-inciting handful — and seem unlikely to publish everything, in the style of WikiLeaks. They are holding onto more secrets than they are exposing, at least for now.

“We have this window into this world, and we’re still trying to understand it,” Poitras said in one of our last conversations. “We’re not trying to keep it a secret, but piece the puzzle together. That’s a project that is going to take time. Our intention is to release what’s in the public interest but also to try to get a handle on what this world is, and then try to communicate that.”

The deepest paradox, of course, is that their effort to understand and expose government surveillance may have condemned them to a lifetime of it.

“Our lives will never be the same,” Poitras said. “I don’t know if I’ll ever be able to live someplace and feel like I have my privacy. That might be just completely gone.”

<nyt_author_id>

Peter Maass is an investigative reporter working on a book about surveillance and privacy.

Editor: Joel Lovell

Slovenski veleposlanik Kirn o razliki med slovensko in ameriško diplomacijo

Veleposlanik Slovenije v ZDA Roman Kirn o naši pobudi, da naj vlada ponudi zaščito Edwardu Snowdnu:

“Kot diplomat Slovenije lahko svetujem veliko opreznost pri takih pobudah. To ni preprosta humanitarna gesta, ampaka klasično politično dejanje. Ihtave, prenagljene, poenostavljene odločitve lahko državi škodujejo. “Na vprašanje ali pomeni slog ameriškega veleposlanika Josepha Mussamelija, da je gubernator in da nas ameriška diplomacija obravnava kot kolonijo Kirn odgovaja: “Tega ne vidim tako, to je zgrešen in poenostavljen predsodek, ki kaže na stereotipna razmišljanja.”

SLOVÉNIE – Quelle crise ?

SLOVÉNIE

Quelle crise ?

Par Catherine Samary *

La Slovénie a été souvent présentée dans les médias depuis la crise chypriote comme le prochain maillon faible de la zone euro, susceptible de faire appel à « l’aide » européenne. Elle affronte une crise réelle, mais qui est exploitée pour faire « passer » les mesures « structurelles » réclamées de façon récurrente par les institutions financières internationales et européennes depuis des années. La mobilisation sociale qui s’est déployée pendant des semaines dans tout le pays au cours de l’hiver, en sourdine aujourd’hui, comporte des atouts exceptionnels et de grandes fragilités. Sa consolidation et son extension détermineront l’issue d’un bras de fer dont les enjeux se situent bien au-delà des deux millions d’habitants du pays.

Les enjeux immédiats : le sauvetage de quoi ?

Malgré une fragile reprise succédant à la forte récession (— 8 %) de 2009, la Slovénie est retombée en récession (— 2,5 %) en 2012 et les pronostics sont pessimistes pour 2013. Le taux de chômage, qui était en dessous de 8 % en 2010 dépasse aujourd’hui les 11 %.

Avant sa chute (sur arrière-fond de scandale pour fraude fiscale) début 2013, le gouvernement de droite de Janez Jansa a créé une structure de défaisance des titres toxiques (« Bad Bank ») dotée d’un plafond de 4 milliards d’euros de ressources garanties par l’État ; le nettoyage des banques est associé à la mise en place d’une Agence unique des participations de l’État (les divers titres financiers qu’il détient) et des engagements de « restructuration » et de « consolidation fiscale » supposées ramener le déficit public actuel vers 0,5 % du PIB en 2015. De premières réformes des retraites et du code du travail, adoptées en décembre 2012, indiquent l’orientation suivie.

Le Fonds monétaire international (FMI) a envoyé en Slovénie une mission qui a livré ses appréciations à la fin de sa visite, en mars 2013 (1). Selon son rapport, la situation alarmante du pays est due à une « spirale négative » mêlant trois composantes : les banques (« en sévère détresse »), les entreprises surendettées et l’État, impliqué de toutes parts et laissant flamber son déficit.

Il y a évidemment du vrai dans cette description : les trois plus grosses banques du pays — dont l’État est le principal actionnaire — ont connu une augmentation de la part de créances douteuses sur l’ensemble de leurs prêts passant de quelque 6 % en 2009 à plus de 20 % en 2012, un tiers des crédits aux entreprises étant, selon ce rapport, non recouvrables. Le FMI estime les besoins de financement du pays à 3 milliards d’euros en 2013 (l’équivalent de 9 % du PIB de ce petit pays de 2 millions d’habitants), dont 1/3 pour la recapitalisation des banques avec pour le gouvernement une échéance très importante de refinancement de sa dette publique en juin 2013, pour un montant d’un milliard d’euros.

Le rapport du FMI soutient et radicalise les premières mesures prises. Mais sa mission dit s’inquiéter du « manque de transparence » et des intérêts croisés opaques sous-jacents à la crise. Elle propose d’y répondre en suggérant d’intégrer aux nouvelles structures mises en place des experts internationaux « indépendants ». Indépendants de qui ?

Le FMI se soucie également d’un « mauvais usage des finances publiques » et déclare, dans son rapport de mars, quelle est sa réponse : « la défense mal conçue de “l’intérêt national” incluant l’hostilité à la vente d’actifs aux étrangers, pèse sur le budget et prolonge de façon excessive la déprime du secteur bancaire et des entreprises. Une privatisation conséquente pourrait fournir un signal puissant aux investisseurs internationaux ». Le discours a le mérite de la clarté.