Kot v tridesetih letih prejšnjega stoletja je vse nastavljeno za katastrofo. Stanje je še mnogo slabše: Thatcher – Reagan (Hoover, laisser faire ali neoliberalizem) poskrbita za krizo. V tridesetih se je vsaj vsaka država lahko reševala po svoje. V EU, še zlasti Evroconi so države talci in morajo izpolnejvati “domače naloge”, za katere se vnaprej ve, da bodo neučikovite. Enosmerna, parcialna poliotika se izvaja zato, ker je Nemčija prevelika in premočna in ima zapleteno psihologijo in ima morda nehote koristi od takega razvoja. Boji se inflacije, gospodinjska mentaliteta jo zavezuje k varčevanju. Levica ne more sestaviti vlade, ker socilademokrati ne marajo sodelovati z LInke. (Stara tradicija iz tridesetih.) Vse je lepo povezano z imperialnimi interesi globalnega, pretežno ameriškega kapitala. Vsaka izmed ogroženih držav je prepruščena sama sebi. EU sadi rožice, rine glavo v pesek, ponavlja mantro o domačih nalogah in o približajoči se katastrofi niti ne govori. Gre za iracionalno, magično, infantilno in prastaro prepričanje, da bo grožnja tako morda izginila. Razumljivo, saj v Evropi prevladuje thatcherjanska desnica, ki jo ne odlikuje zapleteno sistemsko razmišljanje, ampak nagovarja gospodinsko in kmečko pamet. Še večji problem, še bolj odgovorna je alternativa, t.i. levica, ki razen obtoževanja, demonizacije nasprotnikov in prilagajanja njihovim programom (neoliberalnim) ni sposobna ničesar. Še posebej je cepljena proti samokritiki, proti vprašanju, s čim pa mi sami povzročamo tak razvoj. Politična korektnost, danske mesne kroglice in božično drevo v spodnejm članku je lep laboratorisjki vzorec obnašanja evrospke, verjetno tudi svetovne levice. Problem, upravičeno ali neopravičeno doživljanje orgoženih identitet je proglašen za neproblem, za zgolj desničarski fenomen. Zato se ga zamolči ali prepove. Politična korektnost poskrbi, da se vsi problemi, nasprotja in napetosti vstrajno pometajo pod preprogo. Tako pritisk v evropskem loncu nekontrolirano narašča, in nihče se ne ukvarja s trem, kako zmanjšati ogenj in kako katastrofalne bodo polsedice eksplozije. Še kredibilnih akademskih študij na to temo ni. In to kljub temu, da smo vse to že nekoč videli, v predvojni weimarski Nemčiji .

I.K.

Mikkel Dencker, a mayoral candidate in Hvidovre, Denmark, put up campaign posters. He has made the removal of meatballs from kindergarten in deference to Islam a campaign issue.

The issue has become a headache for Mayor Helle Adelborg, whose center-left Social Democratic Party has controlled the town council since the 1920s but now faces an uphill struggle before municipal elections on Nov. 19. “It is very easy to exploit such themes to get votes,” she said. “They take a lot of votes from my party. It is unfair.”

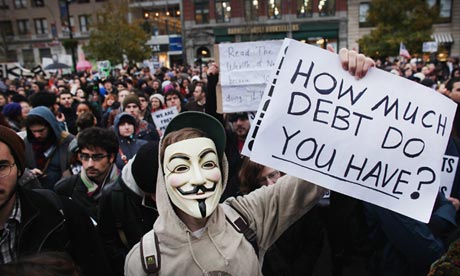

It is also Europe’s new reality. All over, established political forces are losing ground to politicians whom they scorn as fear-mongering populists. In France, according to a recent opinion poll, the far-right National Front has become the country’s most popular party. In other countries — Austria, Britain, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Finland and the Netherlands — disruptive upstart groups are on a roll.

This phenomenon alarms not just national leaders but also officials in Brussels who fear that European Parliament elections next May could substantially tip the balance of power toward nationalists and forces intent on halting or reversing integration within the European Union.

“History reminds us that high unemployment and wrong policies like austerity are an extremely poisonous cocktail,” said Poul Nyrup Rasmussen, a former Danish prime minister and a Social Democrat. “Populists are always there. In good times it is not easy for them to get votes, but in these bad times all their arguments, the easy solutions of populism and nationalism, are getting new ears and votes.”

In some ways, this is Europe’s Tea Party moment — a grass-roots insurgency fired by resentment against a political class that many Europeans see as out of touch. The main difference, however, is that Europe’s populists want to strengthen, not shrink, government and see the welfare state as an integral part of their national identities.

The trend in Europe does not signal the return of fascist demons from the 1930s, except in Greece, where the neo-Nazi party Golden Dawn has promoted openly racist beliefs, and perhaps in Hungary, where the far-right Jobbik party backs a brand of ethnic nationalism suffused with anti-Semitism.

But the soaring fortunes of groups like the Danish People’s Party, which some popularity polls now rank ahead of the Social Democrats, point to a fundamental political shift toward nativist forces fed by a curious mix of right-wing identity politics and left-wing anxieties about the future of the welfare state.

“This is the new normal,” said Flemming Rose, the foreign editor at the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten. “It is a nightmare for traditional political elites and also for Brussels.”

The platform of France’s National Front promotes traditional right-wing causes like law and order and tight controls on immigration but reads in parts like a leftist manifesto. It accuses “big bosses” of promoting open borders so they can import cheap labor to drive down wages. It rails against globalization as a threat to French language and culture, and it opposes any rise in the retirement age or cuts in pensions.

Similarly, in the Netherlands, Geert Wilders, the anti-Islam leader of the Party for Freedom, has mixed attacks on immigration with promises to defend welfare entitlements. “He is the only one who says we don’t have to cut anything,” said Chris Aalberts, a scholar at Erasmus University in Rotterdam and author of a book based on interviews with Mr. Wilders’s supporters. “This is a popular message.”

Mr. Wilders, who has police protection because of death threats from Muslim extremists, is best known for his attacks on Islam and demands that the Quran be banned. These issues, Mr. Aalberts said, “are not a big vote winner,” but they help set him apart from deeply unpopular centrist politicians who talk mainly about budget cuts. The success of populist parties, Mr. Aalberts added, “is more about the collapse of the center than the attractiveness of the alternatives.”

Pia Kjaersgaard, the pioneer of a trend now being felt across Europe, set up the Danish People’s Party in 1995 and began shaping what critics dismissed as a rabble of misfits and racists into a highly disciplined, effective and even mainstream political force.

Ms. Kjaersgaard, a former social worker who led the party until last year, said she rigorously screened membership lists, weeding out anyone with views that might comfort critics who see her party as extremist. She said she had urged a similar cleansing of the ranks in Sweden’s anti-immigration and anti-Brussels movement, the Swedish Democrats, whose early leaders included a former activist in the Nordic Reich Party.

Marine Le Pen, the leader of France’s National Front, has embarked on a similar makeover, rebranding her party as a responsible force untainted by the anti-Semitism and homophobia of its previous leader, her father, Jean-Marie Le Pen, who once described Nazi gas chambers as a “detail of history.” Ms. Le Pen has endorsed several gay activists as candidates for French municipal elections next March.

But a whiff of extremism still lingers, and the Danish People’s Party wants nothing to do with Ms. Le Pen and her followers.

Built on the ruins of a chaotic antitax movement, the Danish People’s Party has evolved into a defender of the welfare state, at least for native Danes. It pioneered “welfare chauvinism,” a cause now embraced by many of Europe’s surging populists, who play on fears that freeloading foreigners are draining pensions and other benefits.

“We always thought the People’s Party was a temporary phenomenon, that they would have their time and then go away,” said Jens Jonatan Steen, a researcher at Cevea, a policy research group affiliated with the Social Democrats. “But they have come to stay.”

“They are politically incorrect and are not accepted by many as part of the mainstream,” he added. “But if you have support from 20 percent of the public, you are mainstream.”

In a recent meeting in the northern Danish town of Skorping, the new leader of the Danish People’s Party, Kristian Thulesen Dahl, criticized Prime Minister Helle Thorning-Schmidt, of the Social Democrats, whose government is trying to trim the welfare system, and spoke about the need to protect the elderly.

The Danish People’s Party and similar political groups, according to Mr. Rasmussen, the former prime minister, benefit from making promises that they do not have to worry about paying for, allowing them to steal welfare policies previously promoted by the left. “This is a new populism that takes on the coat of Social Democratic policies,” he said.

In Hvidovre, Mr. Dencker, the Danish People’s Party mayoral candidate, wants the government in, not out of, people’s lives. Beyond pushing authorities to make meatballs mandatory in public institutions, he has attacked proposals to cut housekeeping services for the elderly and criticized the mayor for canceling one of the two Christmas trees the city usually puts up each December.

Instead, he says, it should put up five Christmas trees.